The Glory of Positive Criticism

(NB: I originally wrote this for the DesignMap blog earlier this year.)

Back in 2003, The Believer magazine debuted. Its centerpiece was an the essay by Heidi Julavits condemning snark and arguing for the benefits of a positive review culture. This was maybe not a big deal to most folks, but for a Brooklyn-dwelling literary nerd (named me) working away at a novel (like I was) and publishing career (you see where this is going), this was big — it instantly polarized everyone I knew and spawned a million happy hour arguments: On one side there was the notion that tearing people down was wrong, and as a community we ought to build one another up — not only was it more pleasant but it resulted in better work. On the other there was what seemed to me at the time a braver, more reasonable stance: nothing would ever get better if you didn’t point out what was wrong about it.

And then, earlier this year, I came across two criticism-focused articles within a few days and was transported the barroom polemics of yesteryear (oú les sont?). Reading An Anatomy of Uncriticism at Print and Jonah Lehrer’s much-discussed New Yorkerarticle on groupthink, I was surprised to find I didn’t feel quite so dedicated to criticism as I once had. Being told what wasn’t working still had a huge place, but years of working as designer had shown me that positive feedback, at least is far as I was on the receiving end, was pretty wonderful.

In a fit of self-consciousness, I tried to reconcile why I liked positive feedback so much when it was applied to me — was it just the ego boost of hearing nice things? or was there something else? — and discovered, much to the gratification of my ego, that there was in fact something else.

Positive feedback made it easier to identify the best next direction and in doing supported my ability to design something both delightful and functional. That is, not only was it nice, but knowing what was evocative or delightful or compelling in what I did helped sparked an atmosphere focused on achieving something beyond functional and inoffensive. For a team it changes the tone and the content and creates an atmosphere of doing better.

Breaking It Down

When presented with feedback on a deliverable from any phase of design, the instant question is “what next?” It may also be “what does this person really mean?” but that is really just a variation on “what next?”—which direction is the best path in our pursuit to shape this design into a product that delights and empowers users, supports stakeholders, and is technically feasible?

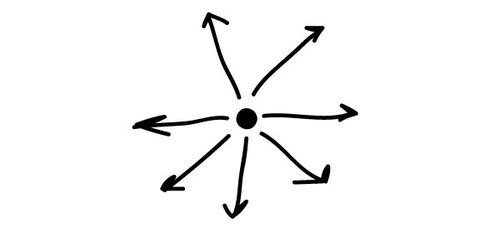

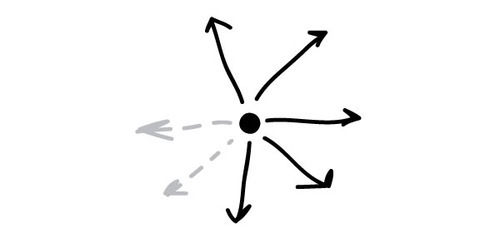

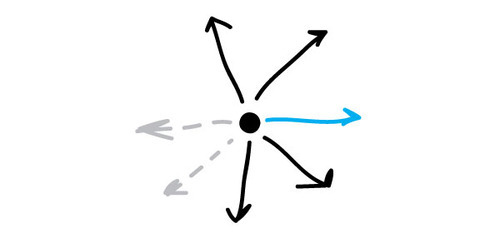

With purely negative feedback one possible path is eliminated. With negative constructive feedback, maybe two or three. We know what not to do.

Empty positive feedback (“Cool”) is about as useless as empty negative feedback. Constructive positive feedback, rather than crossing off one path and leaving many, can highlight one or two “most-correct” options. In conjunction with negative feedback and technical constraints, it is likely that a single direction forward will emerge.

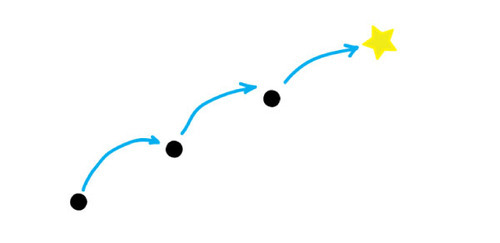

In a series of iterative cycles — across a single deliverable or a full project — this method of identifying the most-correct next step will compound itself, creating a functional, pleasing product while leaving extra time and effort to devote to delight. Or as Jared Spool writes, “The detail not only helps the design owner feel good about what they’ve done, it connects the vision and philosophy to the design itself.”

Really?

Okay, you might be thinking, sure we should be constructive and explain why we say what we say, but isn’t this just the definition of constructive criticism? Perhaps yes, but so often it is easy to only focus on negative feedback and the reasons for said negativity. It is easy to dismiss the bristling that follows as a designer being too sensitive. But there is a reason the balance of positive and negative and the question of respect feature so heavily in articles like Coaching Experience Designers and What Goes Into a Well-Done Critique. It makes designers happy and projects better.

Positive feedback creates an atmosphere of respect. When you comment positively on someone’s work it demonstrates recognition of the effort and thought they have put into their design. No one likes to feel unappreciated, and, as Coaching Experience Designers puts it, “There is nothing more demotivating than to work really hard to produce a creative solution to a problem, only to present it for review, then have others quickly dismiss it.”

Positive feedback also focuses the team on a conversation about excellence. When we know what is excellent, we see opportunities to reveal that excellence throughout the system. Instead of being about how to make insufficient design less-bad, positive feedback frames the challenge as make the design more-good. Not only does this make better design but it makes better design teams — happy designers collaborate better and are less worried about hurt feelings and stepped-on toes. Momentary pain is dismissible when you know you are appreciated. In fact, positive feedback makes it easier to take the necessary negative criticism. At least it does for this particular designer.

Incorporating Positivity

Ready to be more positive? The easiest way is to include more positive feedback into your critiques. You can:

- Consider (or look at) the last version. Point out the changes that moved in the right direction.

- Be specific about what you like and why

- Ask yourself, “What’s the best thing about this design?” Make a habit of pointing that out, even if you feel awkward at first.

- Avoid the word “but”. You may have specific positive feedback, and you should give it. Separating it from the criticism allows each to stand on its own, rather than being diluted by one another. For example, “I really love your dress, but those shoes don’t work with it at all,” versus “I really love your dress! I’m not sure those shoes work with it.” In the former, one is not left with the impression that the dress is that great at all, even if the compliment was genuine.

- Focus on corrective action when you do point out a problem. Move the discussion quickly to improvement (which is exciting).

Another more complicated idea,courtesy of the Intercom blog and Bill Buxton is called walking on both sides of the street.

This process, focused around situations in which multiple solutions are being offered by multiple designers, has each designer takes a turn outlining the situations in which their solution is not ideal and the situations in which other proposed solutions wouldbe. (If you think this is a rare situation, I would challenge you to consider of how many meetings and whiteboard sessions are really about comparing two competing solutions.) Though in small cases, such a process may not be implemented formally, even taking the time to play in your own head can return dividends.

Whichever strategy works best for you, I know you will find a balance of self-criticism and outward focused positivity will lead both to good feelings and good designs — which is the ultimate goal when you go to work everyday. Right?